RIP Roger Ebert, You Would Have Loved Movies

On Letterboxd

On the morning after seeing Die My Love (dir. Lynne Ramsay, 2025), I logged into Letterboxd. A familiar ritual for the online cinephile. I found the movie quite enjoyable. I would “recommend” it. Was it the best movie I’ve ever seen? No, not even close. Frankly it lacked the je ne sais quoi necessary to be a great film, that sense you get, sitting in the theatre, of viewing something truly singular, the sights and sounds imprinting on your consciousness, expanding the dimensions of reality, leaving traces that will haunt you in quiet moments and become points of reference as you navigate the maze of existence. But the movie was good. It let me access complex emotions at a pitch not usually reached in my mundane life, precisely what I expect from a movie.

If I were a different kind of “content creator,” this would be the substance of my review, packaged so as to more effectively grab your attention for a few dozen seconds before you swipe me away to the next short-form video framed in a vertical aspect ratio. Hardly an insightful response to a piece of art, nor a rigorous analysis of the formal aspects of the medium of film. Though I waste plenty of my attention by consuming other people’s affective responses to films, it is not the kind of film criticism worth engaging in, neither as a reader nor as a writer. Nonetheless, reviews of exactly this kind are what get the most attention on TikTok—so much attention, in fact, that an August 15, 2023 article in the New York Times deigned it worthwhile to profile this coterie of “critics.” Don’t call them that, though. They don’t like film critics, and prefer the much more dignified term “reviewer” or, if you must, “influencer.”

I do not have the wherewithal to watch any reviews from these people. The gloss on these particular reviewers suggests we don’t exactly share the same taste. Besides, I don’t like short-form video content, despite Cameron Kozak’s claim that it allows you to “know [the reviewer’s] voice and what they like;” TikToks provide “something personal that people can connect to.” Being someone who reads, I think you can “know someone’s voice” if they are an articulate writer, something Kozak can’t imagine, seeing as he thinks every review written by a critic “almost sounds like a computer wrote it.” I might disdain the thinly-veiled poptimism of Richard Brody or the midwittedness of AO Scott, but at least I can tell a computer didn’t write their reviews.

Dunking on this 23 year old (who has 1.4 million TikTok followers) is not what this is about. Far more odious to me than the opinions of anyone sharing them on TikTok is the credulousness with which the New York Times reports on their supposed cultural value. The entire article is presented as an appraisal of a plucky group of upstart commentators taking on the stodgy establishment of Film Criticism—a fraught possibility, obliquely acknowledged in the piece, given that legacy publications have been cutting their arts departments. The fact that a group of photogenic zillenials sharing their perspective on cinema managed to capture an audience might be impressive if they had the same ambitions as the Cahiers du Cinema or Pauline Kael, a parallel drawn by the author in about as facile a way as possible. But no, there is absolutely no desire on the part of MovieTokkers to elevate the taste of audiences, or to sharpen viewers’ ability to analyze an unfathomably rich artistic medium. In the words of Juju Green AKA Straw Hat Goofy, a MovieTokker who posts for an astonishing 3.6 million followers, he is on a “mission to combat film snobbery” via videos identifying Easter eggs in Pixar movies. This all should appall anyone who cares about the aesthetic possibilities of film, to say nothing of the increasing anti-intellectualism of American life. The whole thing is predicated on the philosophy of “letting people enjoy things,” ie encouraging people to uncritically consume the noxious bullshit churned out by multinational corporations. And I haven’t even gotten to the part where those multinational corporations pay these “reviewers” to post about new releases, a detestable breach of the duty we should expect our critics to honor. But it’s okay, they aren’t critics, they’re influencers, aka advertisers, and advertisers want nothing less than for people to critically evaluate what’s being sold to them. Green literally worked in advertising before managing to support himself with his videos alone, a fact that should discredit him at every turn, but of course, it earns him access to red carpets and exclusive interviews with actors and filmmakers.

I only dwell on this phenomenon as a way to contextualize the role of a would-be film critic in the contemporary world. Sure, you can (and should) avoid TikTok as an avenue of cultural commentary. Isn’t meaningful criticism still possible? Doesn’t the internet provide a stranger, more varied field of discourse? Can’t anyone with an internet connection offer thoughtful responses to the movies they watch, leading people to see movies differently or see different movies than they would have otherwise? This is the long-quaint idea of the internet as a tool fostering intellectual blossoming along democratic principles. A fable that’s been disproven many times over.

However, between the reification around centers of hierarchical control and pitches to the lowest common denominator gaining the higher ground in discourse, there are flashes of that utopian promise to be found. If it weren’t for Letterboxd, I likely would not have heard of nearly as many movies as I have, and I wouldn’t have encountered some of the richest, most unique film criticism currently being written. Not only that, but Letterboxd seems to be one of the few places it’s still possible to be a true-blue weirdo online. Under the guise of reviewing films, some users post long, diaristic Livejournal style blogposts only obliquely connected to the movie at hand; others compile extensive paranoid research of uncertain earnestness, questioning the occult personal connections of cinematic golden calves or speculating that Tom Hanks is a CIA asset. Letterboxd is something of a haven on the internet, where an interest in cinema can lead you to unimagined intellectual, social, and artistic vistas, freed from the most odious aspects of algorithmic social media. For now, at least.

So why is it that when I set down to post a review for Die My Love, I felt utterly disgusted with this activity and the website that promotes it?

When I summarized my affective response to the film above, I sheared off most of the enthusiasm I felt while sitting in the theatre. During my viewing, I noticed myself tempering the visceral reaction the movie provoked in me with an effort to craft that reaction into a capsule review ready to be posted for my meager number of Letterboxd followers. This is a common feeling I have while watching movies, one that I’m ashamed to confess to. How can I write something about this that will 1) be digestible, 2) impress intellectually, 3) get a laugh, or 4) otherwise signal that I’m a wised up cinema watcher, not easily taken in by pseudo-art bullshit while still respecting the proper shibboleths? The desire to post a pithy review on Letterboxd is both a malignancy of the critical faculty and a parasite on my enjoyment of films.

One of the LB users I linked above, pd187, created this list of films on the site. pd187 is notoriously slippery, but here’s a stab at what this list suggests: Letterboxd, as a social media site, despite some insulation from algorithmic pressures typical of the wider ecosystem, is nonetheless inseparable from the same forces that turn everyone posting online into self-conscious constructions optimized for public consumption; that is, everyone online is a good little brand ambassador. The movies listed therein have, deservedly or otherwise, become tokens for signaling one’s belonging to a certain market demographic, like wearing Patagonia or driving a Tesla. Whether or not Heat is a great movie is besides the point. Posting online that you think Heat is a great movie is a secret handshake people have mimetically picked up as a way of identifying themselves as members of the in-group “discerning Letterboxd users.” The importance is not to experience a film as richly as it asks you to, but to appear as though you are someone capable of experiencing a film as richly as others do.

It’s been noted that the most popular reviews on the site rarely indicate deep critical engagement; as with every other social media website, what gets the most attention are glib, sardonic jokes that, to my mind, indicate a fear of exposing oneself in the way earnest criticism requires. Why make potentially noncoterie (or, heaven forbid, earnest and “cringe”) assessments of films when you can make an easy joke, such as:

That way, other users know that you know that Josie & the Pussycats (dir. Harry Elfont, 2001) and They Live (dir. John Carpenter, 1988) are in some way “about” capitalism, without the pesky business of articulating what aspects of each film deal with class consciousness, advertising, the culture industry, conformity, corporate control, etc. You get to feel clever for fitting 9th grade level thematic analysis into a tired joke format; other users get to feel clever for understanding your joke; and the films remain interchangeable objects of consumption. By the way, Guy Debord would be a more apt reference, in both cases, than Karl Marx.

Not that I expect everyone to be a semiotics professor, or that they do Lacanian psychoanalysis of films on a social media website, or even that everyone totally grasp the principles of editing, mise en scene, casting choices, etc. It’s fine to make jokes about movies; I do so myself. What I don’t like about Letterboxd is the effect it has on my own viewing habits. In addition to the site’s tendency to homogenize taste among young cinephiles, it turns the experience of watching movies into a social competition. Whether an average user admits it or not, the statistics that the website aggregates—how many movies you’ve watched, the average ratings of movies, how much engagement your movie reviews earn—do, subconsciously, alter the way you watch movies. Ironically so, given that, in principle, movies are a unifying and anonymizing artistic medium, in which the audience becomes a single mass of bodies harmonized by the lights flashing across a large screen.

Okay, so what am I on about. Am I just irritated by the state of film criticism, irritated by social media, irritated by contemporary audiences? I’m not just those things. If I were, I would ignore TikTok, delete my Letterboxd, and avoid talking to anyone who’s really excited to see the live action Moana. But I’m writing a newsletter because I’m trying to establish what I’m here for, and how to proceed as a movie viewer. In the months since announcing this pivot to film as a subject, I’ve been planning topics for essays so that I can return to a consistent release schedule. One thing I could do that would make consistency easy is write movie reviews. But that feeling of disdain I had when I tried to write a review for a new release revealed that I’d turned my viewing into a compulsive activity, insulated from appreciating film in the way I want to. In a recent newsletter, Rob Horning, talking about AI-generated music, wrote:

What I think I want in my encounters with art is something that will interrupt the consumption feeds that technology has integrated me with — that rhythm of having a very minor interest aroused and disappointed and rekindled again for a cycle that can persist for as long as I surrender to it. Yet instead, I find myself adapting nearly all my listening habits to that cycle, as if all one could ever want is to say “Next.” As much as I might rationalize this mode of listening as a kind of “omnivorous curiosity,” that omnivorousness seems more like indiscriminateness, and the curiosity like distractability.

What Letterboxd has done is install a desire to have seen All the Movies, because then I’ll be a Guy Who’s Seen All the Movies. Writing reviews will, at present, only buttress this frankly stupid ambition. I believe strongly in the importance of film criticism, in all forms of criticism, so long as the ones writing it (and let’s be honest, it’s only worthwhile if it’s written) are dedicated to its literary value. One film critic I admire, AS Hamrah, just published an essay (much to my chagrin) more thoroughly addressing the crises that film criticism faces than I could manage here. In it, he calls critics to arms in the struggle against a culture hellbent on optimizing, and therefor dehumanizing, the entire enterprise of show business. He quotes Delillo’s famous line about the duty of writers:

Writers must oppose systems. It’s important to write against power, corporations, the state, and the whole system of consumption and of debilitating entertainments…. I think writers, by nature, must oppose things, oppose whatever power tries to impose on us.

To be a film critic with any integrity nowadays means opposing the studios’ cowardice, the fait accompli of AI use in production, the pernicious lie that people don’t want to go to the movie theater anymore, and the flattening of culture as a result of the internet.

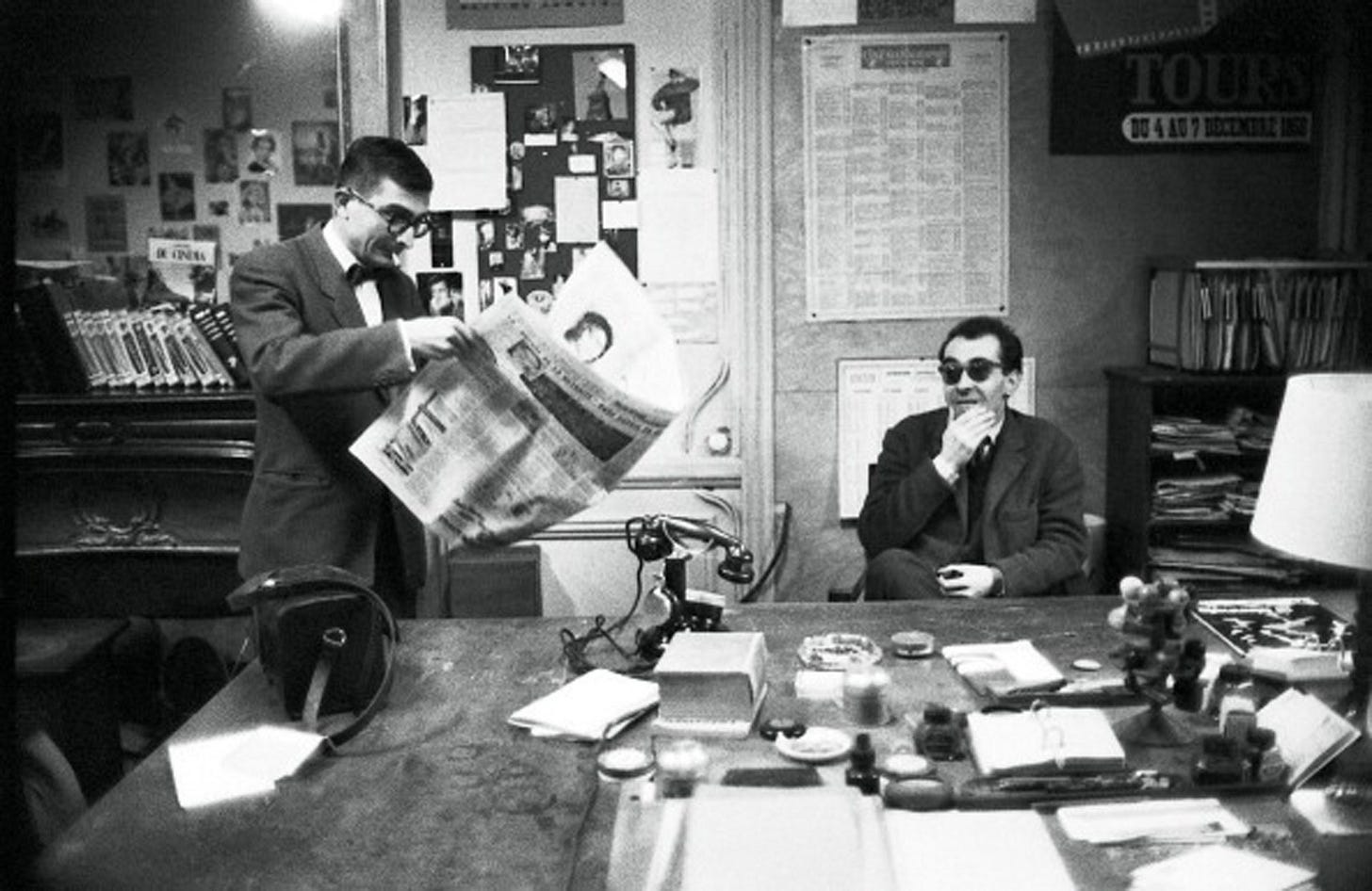

But I don’t want to be a critic. I’m going to make movies. Being an artist doesn’t necessitate being an expert, much less having lots of opinions. I’d much rather be passionate about what I love than be authoritative like a scholar. It was my belief that writing film reviews, a la Jean-Luc Godard, could provide insight into aspects of film I have yet to give much thought, and there’s truth in that. But I distrust anything that encourages me to seek out more instead of finding depth. Besides, from what I can tell, despite trying my damnedest to ignore whatever everyone else on this website is doing, there are plenty of Substacks writing hot takes on One Battle After Another or responses to those hot takes or quote-Notes mocking the responses to the hot takes. I’m not auditioning for a part in that.

The reviews I post here will be more a record of my own film education, idiosyncratic and personal. Since I already boldly declared that I’m going to make movies, I’ll go ahead and announce that moving forward I will be sharing those kinds of homework posts every two weeks, with a longer, more nebulous essay once a month. For now, all of this will be free, but eventually I might paywall the reviews, granted there’s enough interest. If that’s of interest to you, I love you.

i support yr turn towards making movies. making movies with like minds is, despite what any haters might say, very fun.

this essay seems motivated too by the more general writerly anxiety induced by regular internet use that could be summed up like this: "must i write about something in order for it to have been meaningful, valuable, or real?" (pics / thoughts or it didn't happen.) i think it is a natural impulse among writers to anticipate converting their experiences into writing, but the economic and social "benefit" of doing so is what throws that impulse into turbo time. having returned to writing criticism lately, i've tried to shortcircuit that impulse a bit by telling myself to "just" experience a text and then to only write about it if i a) want to spend more time with it and b) want to encourage other people to read it (or to ignore it). then the work of anticipating and writing and translating my private experience to a public presentation becomes more about *helping* myself and others rather than proving some claim whose truth i am already confident abt (namely: that i'm smart and have good taste [much of the time]). critic as guide rather than critic as performer (fuck the metrics).

in other words, this is me encouraging you to know that you are smart and have good taste (much of the time) so as to spend more time helping yrself and others (by writing abt movies and making them) and less time covering your tracks.

i'll be followin along!