Staring down the long, difficult road of the 21st century, an artist would be forgiven for lacking nerve. Nuclear war and mass industrialized murder, the twin evils that defined the 20th century, still loom like terrible dragons above the landscape; the rapid deterioration of environmental conditions, a direct result of those satanic pursuits, continues to immanentize the culture of death presently dictating the course of society. Forget how one is supposed to make art in these conditions: how is one supposed to live?

Norman Mailer posed a version of this question in the wake of World War II, an epoch that he says "presented a mirror to the human condition which blinded anyone who looked into it." The memories of Auschwitz and Hiroshima no longer hold their sharp edges, but the damage wrought on the social landscape remains. If it is possible to die suddenly in a surprise atomic blast; if it is possible to be arbitrarily rounded up and hauled off to a human slaughterhouse; if, now, it is possible to be drowned in a freak hurricane or burned alive in a megafire; if all these atrocities are possible, and only possible due to the actions of humans, then one must squarely face the possibility that within one's own soul lies the source of these evils. Perhaps, if one were to do an honest self-appraisal under these conditions, then a course might be charted, and a bulwark against the buffeting vagaries of the death machine erected, such that a path forward may be cleared.

Skipping past what's worth considering about Mailer's argument, there are many issues to take with the essay "The White Negro," not least being its decidedly unwoke title. Unsurprisingly, though disappointingly, in his attempt to empathize with America's subaltern, and to see in the experience of Blacks an example to emulate, Mailer falls victim to blind spots all too common among white men. To him, it was simply a given that Black men possess preternatural style along with a violent eroticism, two damaging stereotypes with origins in minstrelsy and the propaganda of slave-hunting posses. So not only is it jarring to read Mailer take violent eroticism and pathologize it into a semi-mythic figure/moral exemplar he calls the Psychopath, the whole idea is based on a misappropriation of racist tropes, which pretty critically undermines the argument he's making.

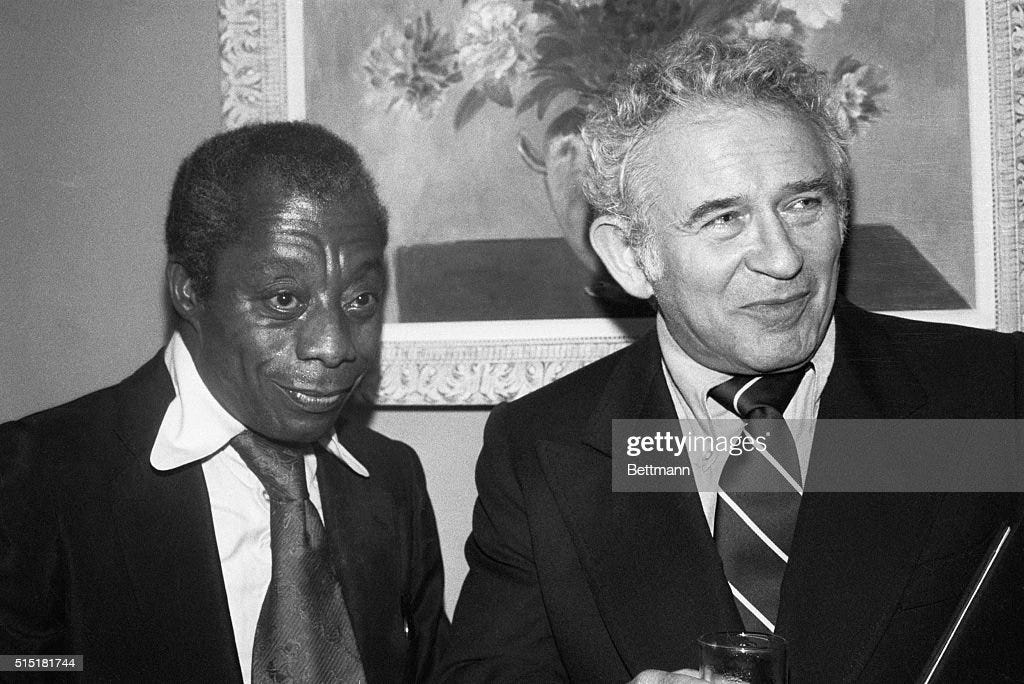

Not that his argument is super coherent anyway. James Baldwin calls "The White Negro" "impenetrable" in an essay detailing his complicated relationship with Mailer, entitled "The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy." To wit, Mailer writes:

Given its emphasis on complexity, Hip abdicates from any conventional moral responsibility because it would argue that the results of our actions are unforeseeable, and so we cannot know if we do good or bad, we cannot even know (in the Joycean sense of the good and the bad) whether unforeseeable, and so we cannot know if we do good or bad, we cannot be certain that we have given them energy, and indeed if we could, there would still be no idea of what ultimately they would do with it.

Pardon? What? the fuck? did you just say Norm? Maybe some of the confusion is due to this shoddy transcription, but what does "Joycean sense of the good and the bad" refer to? Given "them" energy? Who's them? Huh? No entiendo.

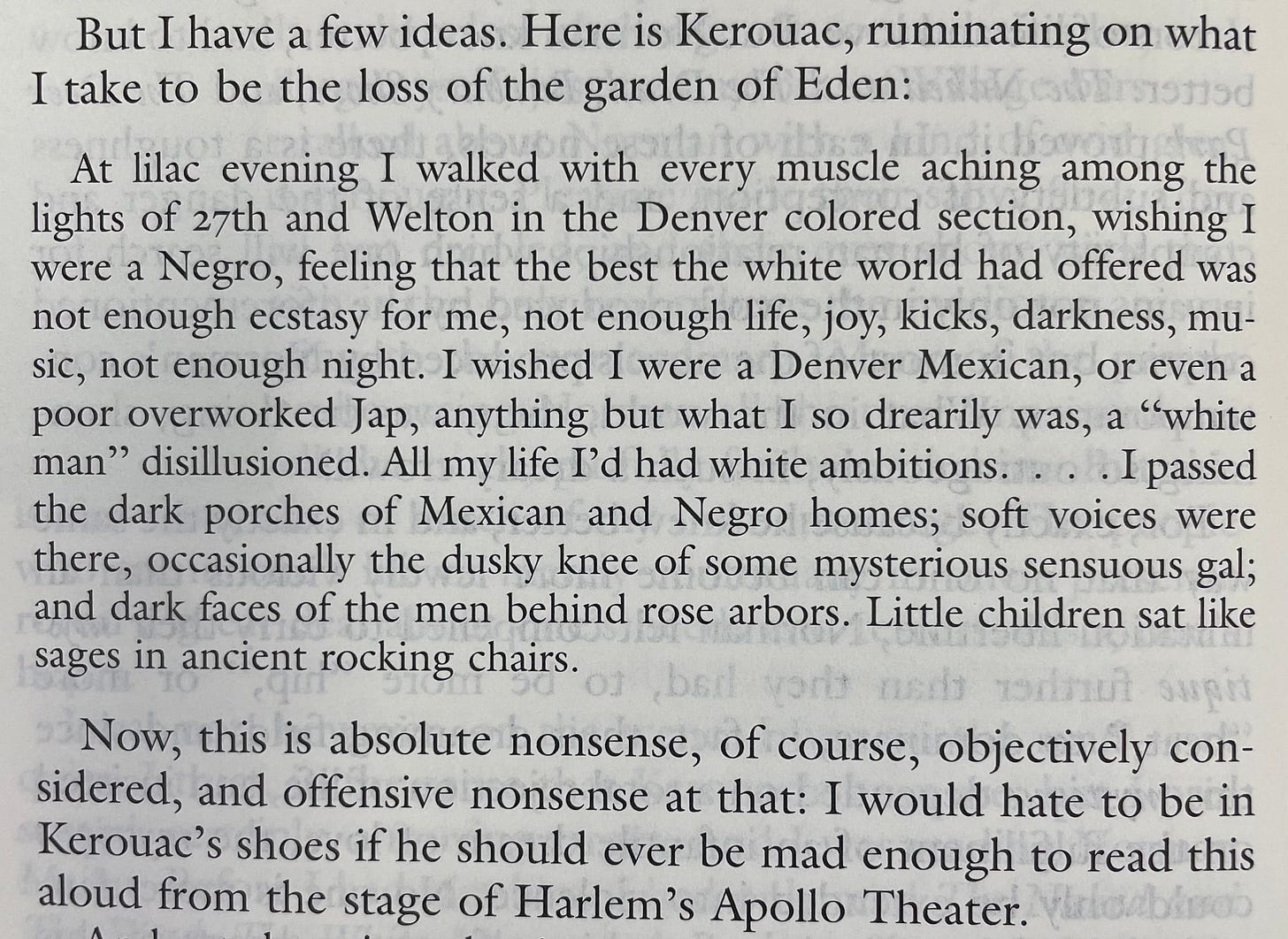

At the heart of the essay is admiration for "the Hip," as in what "hipsters" are "on to" that makes them hipsters. Which, to be fair to Norm here, "hipster" did initially refer to whites adopting the affect and signifiers typical of underground, i.e. Black, jazz clubs. But it's telling that "The White Negro" received criticism both from Baldwin, an actual Black bohemian, and also from Ginsberg and Kerouac, who thought Mailer was just about the squarest cat around. All the funnier that Baldwin takes Mailer to task for wasting his talents trying to pantomime the puerile antics of Kerouac. As an illuminating aside, please enjoy this passage in which Baldwin mercilessly dunks on the Beaten Prince:

What Kerouac says here is basically what Mailer seems to be arguing in "The White Negro," only that Mailer's case is served with a patina of Freudian-Marxist intellectualism: if only I were Black, then my despair would be meaningful. Both Mailer and Kerouac partake in a myth that Baldwin says is uniquely white, the myth of innocence lost. To someone whom the violence and exploitation of industrialized society benefits, if any realization about the death machine ever occurs, it is felt as disillusionment. But for the oppressed and marginalized, innocence is a luxury that cannot be afforded. So really the premise of Mailer's argument is unfounded, because for many people, the atrocities that serve as his point of departure were not at all surprising. Instead, Hiroshima and Auschwitz were merely the logical culmination of the same ideology that motivated the slave trade, Jim Crow, and Manifest Destiny.

Aside from the all-too-American racism, Mailer's opinion of his archetypal Psychopath is so ambiguous as to be unproductive. It only calls to mind another treatment of the archetype of the Psychopath, a characterization that seems to confirm, albeit ironically, Mailer's prophecy that "the psychopath may indeed be the perverted and dangerous front-runner of a new kind of personality which could become the central expression of human nature before the twentieth century is over." In Cady Noland's essay Toward a Metalanguage of Evil, the installation artist outlines the system that facilitates the psychopath's behavior, behavior which she mentions has been compared to the "societally sanctioned characteristics of the entrepreneurial male." To put it another way, contemporary capitalist subjectivity, with its emphasis on self-interested and self-directed economic motivation with an attendant erosion of social ties, is psychopathic, therefore, naturally, a psychopath would be best suited to gaining advantage under its reign.

So what of Mailer's belief in the Psychopath's potential to explode "those mutually contradictory inhibitions upon violence and love which civilization has exacted of us?" Well, being a white boy who required a road to Damascus moment of disillusionment with American society, Mailer failed to appreciate that "civilization" does not inhibit violence. On the contrary, modern society is predicated on violence—towards people of color, towards women, towards queer folks, towards the poor, towards the environment, and therefore everyone. Bearing this in mind, when Mailer talks about social taboos on violence, one finds it difficult to refrain from calling bullshit, to say nothing of the wife stabbing incident.

But, regardless of the moral valence Mailer himself places on whatever he meant by the Psychopath, he's not exactly wrong. Any accounting of the midcentury counterculture's effect on the mainstream would be remiss in overlooking how well the self-indulgent hedonism of the hippies at the very least rhymes with the neoliberal impulse to seek fulfillment through material consumption and "authenticity." Rather than provide an alternative to the stifling conformity of the post-war economy, the hipster, and Mailer's Psychopath, became another vehicle for capitalism's continuous reification.

"TRAP IS THE ONLY MUSIC that sounds like what living in contemporary America feels like. It is the soundtrack of the dissocialized subject that neoliberalism made. It is the funeral music that the Reagan revolution deserves."

- "Notes on Trap," Jesse McCarthy

And, despite bricking it about as hard as he could, Mailer isn’t at all wrong to suggest that Black people and African-American culture are examples of how to live in a world hellbent on your destruction. A common refrain among well-meaning liberals is how they need to educate themselves on institutional racism. In recent years there's been a move towards privileging the perspective of marginalized people when issues such as race come up—"lived experience" discourse. No one can deny the importance of emphasizing that experience in these discussions, because no doubt the marginalized have been routinely, systematically silenced for millennia (hence "marginalized") and recent efforts to create space for those voices is noble, and welcomed.

However, too often, online, in the Media, identitarian conceptions of politics serve to further entrench people into segregated categories. A white person thinks they can never "truly" understand what it's like to be Black (or Latinx, or Chinese, or...), and makes sure to continuously remind themselves (and others) of this impossibility while they're busy "educating themselves" reading White Fragility, all to feel "hip" to "the jive" when watching Hamilton on Disney+. Or, discussions about exploitation are liable to be derailed when someone points out that someone else making cogent arguments doesn't have the authority to do so, since the interlocutor is white, or something equally ad hominem. Look, he's just pointing out how weird it is that the CIA's rebrand mirrors corporate PR campaigns foregrounding "diversity" and "inclusivity," as if 1) it would be Good to have the CIA staffed with more POC, and 2) the CIA could ever be anything more than a toy chest for freak WASPs to play Empire with. These terms, as in "of engagement," have created impediments to solidarity, despite suggesting greater appreciation for the variety of experience. But a guy who was raised by a Fed and probably has some weird things on his resume would think that.

Intersectional analysis is important for highlighting how systems of oppression compound when marginalized identities overlap—a Black trans sex worker is far more likely to face legal, medical, social, political difficulties than a white accountant. But also, simultaneously, somewhat counterintuitively, such analysis ought to reveal that, at base, all of us are constantly being exploited by systems of violence, regardless of identity. That, in fact, “identity” is a by-product of exploitation, oppression, repression, and violence. Like they say, all men are Jews, though few know it. Er, well. People. All people are Jews. Sorry.

At the risk of perpetuating stereotypes, African-American culture does have a lot to admire if one wanted to persevere despite intolerable, often literally unlivable conditions. "Raw talent, charisma, endurance, persistence, improvisation, dexterity, adaptability, beauty," according to Jesse McCarthy, all count among its virtues, though this list comes in context of the ways trap music as a pop culture product harnesses these qualities "to change the attitudes, behaviors, and preferences of others."

McCarthy claims, rightfully, that "[trap] is likely the only literature that will capture the structure of feeling of the period in which it was produced, and it is certainly the only American literature of any kind that can truly claim to have a popular following across all races and classes." If you haven't already, I very strongly urge you to read Jesse McCarthy's essay "Notes on Trap," one of the few truly impressive works of nonfiction writing published in the last few years. There’s a lot more to say about language and rap music, but I think I wrote plenty for how much y’all are paying me.

Check out my SoundCloud page, DJ Podcaster Boyfriend AKA MC PsyOp AKA Mr. Radicalize Your Girl AKA L'Éminence Greige AKA Yung Barna Min-Bae-Lee. Make sure to like and subscribe.